The Medical College opened in 1824 under the auspices of the Medical Society of South Carolina. The first building was erected in 1826 at the corner of Queen and Back Streets and consisted of a dissecting room, medical museum, library, and lecture halls. By 1886, the Medical College had grown to include the School of Pharmacy (1881) and the School of Nursing (1882).

The Medical College facilities were so badly damaged during the earthquake that they couldn’t be used for more than a year. Classes were moved to new wooden structures and to the former U.S. Marine Hospital around the corner from the college on Franklin Street, which had been abandoned after the Civil War because of damage. The Medical College called the structure “a temporary and uncomfortable building.”

The year before the quake, 1885-86, there were 73 students enrolled at the Medical College with 18 graduating in the spring of 1886. Between the time of the earthquake and the start of classes in October 1886, the number of students at the Medical College dropped dramatically to 55 students. However, despite this lower enrollment, the number of students who graduated in 1887 was the same as in 1886: 18. Although the number of students enrolled at the Medical College rose to 62 in October 1887, enrollment was depressed for many years. The 1888-89 circular (Catalogue for 1887-1888) acknowledged that many South Carolina students had left the state after the earthquake to seek medical education elsewhere.

In January 1887 the legislature appropriated $5,000 for the school’s restoration and an additional $5,052 was raised by public subscription. In the spring of 1887 the repairs were completed and the school returned to its old home. School officials raved in the 1887-1888 Catalogue about the restored building: “It affords better facilities for instruction than ever before, it is more comfortable for teacher and student, and is destined, we think, long to subserve [sic] the useful purposes for which it was originally designed. Out of the disaster . . . has come further good and increased advantages.”

News and Courier, Friday, September 10, 1886:

“The roof is in a very dilapidated condition, and liable to blow over into the street. Should be taken down immediately.”

News and Courier, Wednesday, September 18, 1886:

“Notwithstanding the great damage to the Medical College of South Carolina, which will cost a great deal in repairs, the faculty announce that the regular exercises will be resumed on October 15 as usual, and will be conducted in the College building if safe, and if not, then in the most convenient quarters that can be procured. The College deserves the hearty support of the people of the State as a long established institution from which a very large proportion of our physicians have been graduated. Much more should it be supported by the people of our city, to whom it brings annually some one hundred thousand dollars, and for whom [illegible] makes friends and customers in all parts of this State and neighboring States, from which students come and whither are returned capable and accomplished physicians.”

The faculty of the Medical College in 1886 included:

- John L. Dawson Jr., assistant demonstrator and prosecutor of anatomy

- P. Gourdin DeSaussure, instructor in microscopy

- Juan Guitéras, clinical lecturer on physical diagnosis

- G. G. Kinloch, prosecutor of surgery

- R. A. Kinloch, professor of the principles and practices of surgery and clinical surgery

- Allard Memminger, professor of chemistry

- Middleton Michel, professor of physiology

- Francis L. Parker, professor of anatomy

- F. Peyre Porcher, professor of materia medica and therapeutics

- J. Ford Prioleau, dean and professor of obstetrics and gynecology

- R. Barnwell Rhett, demonstrator of anatomy

- T. Grange Simons, acting professor of pathology and practice of medicine

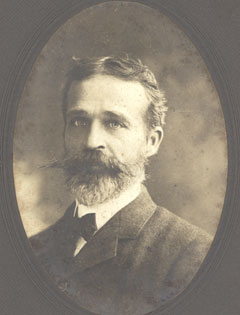

John L. Dawson Jr., assistant demonstrator and prosector of anatomy

Dr. Dawson was born September 29, 1859, son of John L. Dawson, M.D. He graduated from the College of Charleston, A.B., in 1878 and in 1881 when he graduated from the Medical College of the State of South Carolina, he received at the same time the degree of master of arts from the College of Charleston. For some years following his graduation he assisted in the dissecting room at the Medical College and n 1887 was elected demonstrator of anatomy; in 1890 he achieved the chair of professor of the practice of medicine. In his connection at the Medical College he held a variety of posts, being at one time clinical assistant in disease of the eye and ear, assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics, professor of the practice of medicine and finally emeritus professor of medicine from 1915 until his death in 1917.

Dr. Dawson was well known as a practitioner and particularly as a diagnostician, in which role he excelled. He served as recording secretary of the South Carolina Medical Association fro ten years and was its president in 1909. He was also president of the Medical Society of South Carolina in 1908-1910, and president of the National Association for the Study of Prevention of Tuberculosis. He attended many congresses and meetings, both in this country and abroad, pursuing particularly his interest in activation of measures against tuberculosis. With Dr. Robert Wilson of Charleston and Dr. Edward McGahan of Aiken he was representative to the National Tuberculosis Association from South Carolina.

The John L. Dawson Clinical Society, a student organization, was named in his honor and was active at the Medical College for many years. He contributed some ten papers to the medical literature. Among them was a particularly profound address on “The Need of Better Education in the Preparation for the Study of Medicine,” in which he pleaded for a general cultural education of the medical student.

Despite his varied activities, Dr. Dawson was essentially a general practitioner, and it was as such that his remarkable personality and exceptional skill exercised their widest influence. He was of a singularly lovable and attractive personality, appealing and sympathetic, with a keen sense of humor which he exhibited in his admirable quality as raconteur. More than this, he was loyal, charitable, trustworthy, and possessed of numerous firm friends.

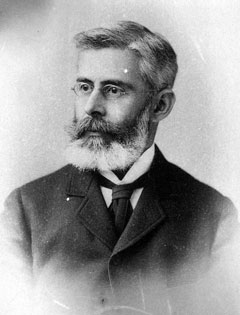

P. Gourdin DeSaussure, instructor in microscopy

Dr. deSaussure was born in Charleston on March 23, 1857. He served on the house staff

of the City Hospital at Charleston while still an undergraduate medical student and

graduated at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1877. As he was under the required age of 21 he did not receive his degree until 1878. He served as a volunteer with the Howard Association during the great yellow fever epidemic of 1878 in Memphis and afterwards studied at the Woman’s Hospital in New York under J. Marion Sims and T. Gaillard Thomas. Declining offers in New York, he returned to Charleston and was appointed prosector in anatomy in 1882 and later in 1883 became assistant professor of gynecology and abdominal surgery. During the epidemic of yellow fever at Brunswick, Georgia, he served as a volunteer physician.

Dr. deSaussure was a frequent writer and used the microscope assiduously in a day when

it was in comparatively little use. He was secretary of the Medical Society of South

Carolina for some years and later became its president. He instigated the establishment of

the Holiday House on Sullivan’s Island which was used as a summer retreat for women

and children of small income and engaged in many public services which endeared him

to the community.

Juan Guitéras, clinical lecturer on physical diagnosis

Juan Guitéras was born on January 4, 1852 in Cuba. Guiteras studied medicine at the University of Havana, and moved to the United States in 1873 to attend the University of Pennsylvania, from which he graduated that same year. He worked at Philadelphia Hospital until 1879, when he went into the U.S. Navy as a physician and began to research yellow fever, working with Stanfard Chaille and George Miller Sternberg in the Havana Yellow Fever Commission. On May 5, 1883 he married Dolores Gener in Cuba. He was clinical lecturer on physical diagnosis at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina from 1884 to 1888, after which he left to teach at the University of Pennsylvania from 1889 to 1898. When the Spanish-American War broke out, Guiteras went to Cuba with the U.S. Army and joined the yellow fever research team led by William C. Gorgas. Guitéras was a pathologist specializing in yellow fever. In 1900 he became chair of the Pathology and Tropical Diseases department at the University of Havana and founded the Journal of Tropical Medicine. In 1902 he became director of the Cuban Department of Public Health and continued research in pathology. He was a member of the Yellow Fever Commission of the International Health Board in 1916. He died October 28, 1925 in Cuba.

G. G. Kinloch, prosector of surgery

The son of Dr. R. A. Kinloch, Dr. George Kinloch was graduated from the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1881, being the first honor man and valedictorian of his class. He then entered Roper Hospital as a house physician, afterwards taking post-graduate work in microscopy in New York, and spending three years in Austria and Germany before returning to Charleston. While in Europe he translated Ultzmann on Pyuria but was forestalled in his publication by the appearance of another translation.

He was taken into partnership with his father and was a skillful surgeon. At the Medical College he filled the chair of microscopy and was subsequently assistant professor of surgery (1885). The obituary notice given to Dr. Kinloch in the Medical Society would indicate that he was considered an extremely desirable and promising physician. Born December 19, 1859 and died on June 7, 1886 (before the earthquake).

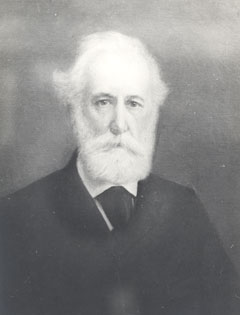

R. A. Kinloch, professor of the principles and practices of surgery and clinical surgery

Dr. Robert Alexander Kinloch was born in Charleston on February 20, 1826. He was graduated from the College of Charleston in 1845 with distinction. After one “course” at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina he took his Medical Degree from the University of Pennsylvania (1848), then spent two years in the hospitals of Paris, London and Edinburgh. Returning home, he began to practice in his native city, but when the War broke out, he entered the Confederate army as a surgeon (July, 1861). During his military career he served at various times upon the staffs of Generals Lee, Pemberton, and Beauregard and was also detailed as a member of the medical examining board at Norfolk, at Richmond, and at Charleston. Subsequently, he held the position of inspector of hospitals for South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Upon the close of the War he resumed practice in Charleston and in 1866 was elected to the chair of materia medica in the Medical College of the State of South Carolina. He was First Surgeon at Roper Hospital and also attended in City Hospital, and later in St. Francis Infirmary.

In 1869 he was transferred to the chair of the Principles and Practice of Surgery and subsequently to that of Clinical Surgery, which he occupied to the time of his death. In 1888 he was elected dean of the faculty and continued to serve until he died. He was president of the Medical Society of South Carolina, a founder of the American Surgical Association in 1880, and an associate fellow of the Philadelphia College of Physicians. He was also active in the American Medical Association and was its First Vice President in 1884. For a short time he served as editor of the Charleston Medical Journal, in which he published many of his surgical contributions. He resigned in 1874. He was president of the South Carolina Medical Association in 1884.

Dr. Kinloch was considered to be a very able surgeon, bold and determined, possessed of a rare skill in execution and perfect poise in the face of unforeseen emergencies. He was reputed to be the first in the United States to resect the knee-joint for chronic disease, his operation preceding that of Dr. Gross by three or four months, and also the first to treat fractures of the lower jaw and other bones by wiring the fragments, and among the first to perform a laparotomy for gunshot wounds of the abdomen without protrusion of the viscera. This last operation was performed at Summerville some four months after the original injury. He also invented an urethratome, a stricture dilator, and a stem pessary. He wrote many papers.

As a professor and as dean Dr. Kinloch strove to elevate the standards of medical education and chafed under restrictions which he could not overcome. He once said, “The standard of the College could and should be elevated. It is painful for me to make such an announcement. It is more painful for me to say that I am powerless to improve the situation.”

Dr. Kinloch was a chronic sufferer from dyspepsia and heart disease. He died of pneumonia following an attack of influenza on December 23, 1891.

Allard Memminger, professor of chemistry

Dr. Memminger was born in Charleston to CSA secretary of treasury C.G. Memminger and Mary Withers (Wilkinson) Memminger on September 30, 1854. He graduated from the University of Virginia and received his medical degree from the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1880. After graduation he joined the faculty of the Medical College and rose to the position of professor of chemistry and hygiene and clinical urinary diagnosis. He also served as dean of the College of Medicine in 1908. Dr. Memminger served as chairman of the state board of pharmaceutical examiners, as well as the chairman of the Charleston board of health. He was a fellow of the American Medical Association, as well as many other professional organizations in South Carolina and abroad. He died in 1937 at age 83 in Charleston.

Middleton Michel, professor of physiology

William Middleton Michel came of a medical line. His grandfather Francis, of Port au Prince, practiced for a time in Charleston. His father, William Daniel Michel, 1795-1869, who received his medical education in Paris and served in the Napoleonic Wars, practiced in Charleston and was co-editor of the short-lived Carolina Journal of Medicine, Science and Agriculture. His brother Fraser Michel, practiced in Charleston and later in Alabama.

Middleton Michel received his preliminary training in Pension Labrousse and studied medicine in Paris under some of the famous men of the time, such as Richet, Coste, Cruveilhier and Longet. He served as a dissector for Cruveilhier and lectured on anatomy at the request of Richet. After spending five years in Paris, he received his diploma from the Ecole de Medicine. Returning to Charleston, he graduated from the Medical College there in 1846 and immediately entered into those many activities which made him so prominent in medical affairs in the city.

He was the founder of the Charleston Summer Medical Institute (1848), a private school which he conducted practically alone, lecturing on anatomy, physiology and obstetrics. The session of this school included the months of April through July. It achieved quite a success, at times having as many as 150 students. The Civil War forced its permanent closing.

Leaving his school for service in the Confederacy, Dr. Michel acted as consulting surgeon at Manchester and Richmond in Virginia. After the War, upon the reorganization of the Medical College, he joined its faculty and from 1868 until his death in 1894 he served as a teacher of physiology, medical jurisprudence and histology. He was elected surgeon to the City Hospital in 1871 and in 1880 he became president of the Medical Society of South Carolina. He was active in the Charleston Board of Health and was a member from 1880 until 1894.

Dr. Michel was a man of literary cast. During the War he edited the Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal, 1863-1864. Later in Charleston he was co-editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. He wrote many papers and was particularly interested in the pituitary body. He was an able linguist and a member of many learned societies. On one occasion he held a debate with Agassiz concerning the opossum. During his career he was offered professorial positions in seven institutions outside the state. Dr. Michel was possessed of great intellect, so much so that he lectured in every chair of the Medical College with equal capacity and effectiveness.

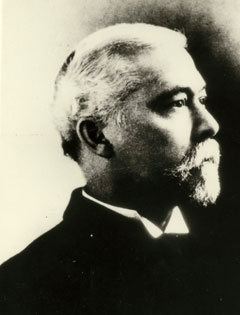

Francis L. Parker, professor of anatomy

Dr. Parker was born in Abbeville District in 1836 and received his education at the South Carolina Military Academy, where he graduated in 1855. He received his medical degree at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1858 after a preceptorship under Dr. Henry R. Frost, his uncle. After graduation he served in the Roper Hospital, where he tended the yellow fever patients of 1858 and himself contracted the disease. In 1858 he became assistant demonstrator in the Medical College, demonstrator of anatomy in 1866, and later (1870) professor of anatomy. The last position he occupied for many years.

Dr. Parker entered the Confederate medical service promptly and served four years of active duty, at first on Morris Island during the bombardment of Fort Sumter, later at Manassas Junction, and finally as surgeon in charge of the South Carolina Hospital at Manchester, Virginia. He then was commissioned surgeon and assigned to the staff of Commodore Page of the Confederate States Navy in the James River, but desiring more active service, obtained a transfer to the Hampton Legion and served through many of the great battles of the War.

Returning to Charleston, he resumed his practice and his connection with the Medical College, being one of the small number who at great personal sacrifice maintained the life of the college during its most critical postwar period. He became particularly interested in diseases of the eye and ear. In 1891 he was elected dean of the faculty, in which position he served until his retirement in 1906.

Dr. Parker, at one time editor of the Charleston Medical Journal (1875), was the author of numerous articles on general surgery and on the diseases of the eye, ear, nose and throat. He is credited with being the first surgeon to suture a nerve. He was president of the Medical Society of South Carolina (1878), president of the South Carolina Medical Association (1882), and the Association of Medical Officers of the Confederate Army and Navy (1900). He served as attending durgeon or physician to several institutions of the city. The honorary degree of LL.D. was conferred upon him by the University of South Carolina at its centennial celebration in 1905. He died in1913.

Dr. Parker’s ability as a surgeon was recognized throughout the state and he made frequent excursions to distant points to perform his operations. He was much beloved as a teacher and friend.

F. Peyre Porcher, professor of materia medica and therapeutics

Francis Peyre Porcher was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on December 14, 1824 to William and Isabella Sarah Peyre Porcher. Through his mother's side, he was a descendant of the botanist Thomas Walter, author of Flora Caroliniana, the first catalog of the flowering plants of South Carolina, published in 1788. Porcher graduated from the South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) in 1844 and from the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1847. After graduation Porcher spent two years traveling in Europe. Upon his return to Charleston he entered practice, and in 1852, with Dr. E. Belin Flagg, opened the Charleston Preparatory Medical School of the Medical College and lectured on materia medica and therapeutics. During his long affiliation with the Medical College, Porcher served as professor of clinical medicine and chair of materia medica, which position he held from 1874 to 1891. He served as editor of the Charleston Medical Journal and Review and served as president of the South Carolina Medical Association, the Medical Society of South Carolina, and as vice-president of the American Medical Association. During the Civil War, Porcher served as a surgeon in the Confederate Army in Virginia and was detailed by C.S.A Surgeon General Samuel Preston Moore to write, Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, a handbook which identified local plants with therapeutic qualities that could be used in place of manufactured drugs made unavailable because of the Union blockade. Porcher died on November 19, 1895 in Charleston.

J. Ford Prioleau, dean and professor of obstetrics and gynecology

Dr. Jacob Ford Prioleau was born in Charleston in 1826 and attended the College of Charleston. He studied medicine under his father, Dr. T. G. Prioleau, and graduated at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1847. He afterward attended lectures in New York and Philadelphia. Moving to California for a brief period, he returned to Charleston in 1851 and soon became connected with the Charleston Preparatory Medical School, where he lectured on obstetrics and gynecology. He was physician to the Alms House and Roper Hospital. Upon the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the Confederate Army as surgeon of the 12th South Carolina Volunteers, helped organize hospitals, and eventually was taken prisoner. Later he served at the Fairground Hospital in Columbia and the Academy Hospital in Chester (1865). In 1871 he became professor of obstetrics in the Medical College, and a few years later was appointed dean of that institution, which position he held until his death in 1888. He was a member of the Executive Committee of the State Board of Health for many years. The Medical Society of South Carolina elected him president in 1871 and 1872.

Dr. Prioleau contributed to the American Journal of the Medical Sciences and other publications. He was held in high esteem in Charleston.

R. Barnwell Rhett, demonstrator of anatomy

Dr. Rhett, son of the well known Charleston editor, R. Barnwell Rhett, was born near Huntsville, Alabama, and moved with his father to Charleston after the Civil War. He attended the Virginia Military Institute for a time, but because of financial difficulties found it necessary to seek work in Denver, Colorado. But the work was not available and he made his way back to Nashville, largely on foot, and later came to Charleston, where he served for a time as drillmaster to the police force and as house physician in the City Hospital. He graduated from the local medical school in 1879 and became City Dispensary Physician. In 1880 he began to serve as demonstrator of anatomy at the Medical College, in the meantime building a practice and earning an immense popularity. He was competent in surgery of various kinds and was the pioneer in Charleston of a number of surgical procedures. He was also esteemed as an excellent diagnostician.

In 1898 he volunteered to treat the United States Troops at the City Hospital and Riverside Infirmary and achieved a remarkably successful record with them. Dr. Rhett was a beloved family physician who was the epitome of the Southern gentleman. He was known for his generosity to his patients and his small concern for financial reward. He was at one time president of the Medical Society of South Carolina, Dean of the Charleston Medical School, and belonged to other medical organizations. A number of his papers were published. A memorial tablet to him was erected by the City of Charleston in the City Hospital and was later transferred to Roper Hospital.

T. Grange Simons, acting professor of pathology and practice of medicine

Thomas Grange Simons was born in Charleston of French Huguenot ancestry. He saw service during the Civil War as a member of the Washington Light Infantry of Charleston and was wounded three times. He attended the College of Charleston, and after studying medicine with Dr. W. H. Huger, graduated at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1867. Shortly afterward he identified himself with the various medical organizations of the city and was at one time City Physician and Physician to the Charleston City Hospital. He served as president of the Medical Society of South Carolina and was also president of the “Widows and Orphans” Society in Charleston. In state medical affairs he was prominent as president of the South Carolina Medical Association, as chairman of the State Board of Health, and as a member of the Board of Medical Examiners.

Dr. Simons served also as demonstrator in anatomy at the Medical College and physician to the dispensary. Later he held the position of assistant professor of pathology and practice of medicine and finally assumed the chair of materia medica. He was the author of a number of papers.

During the yellow fever epidemics in Fernandina, Florida, in 1876 and in Memphis in 1878, Dr. Simons volunteered his services and rendered valuable aid to the victims. He was greatly interested in public health and was instrumental in the establishment of national quarantine regulations and in the development of a sewage disposal system in Charleston. He was active in the business of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Simons received an LL.D. from the College of Charleston in 1925.

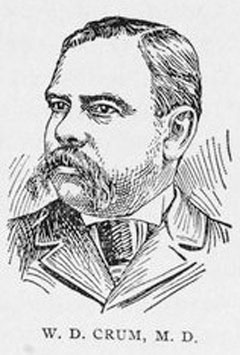

Dr. William Demosthenes Crum

Dr. William Demosthenes Crum, 1859–1912. The son of a white father and a free black mother, Crum attended medical school in the North. There he married Ellen Craft, the daughter of William and Ellen Craft, fugitive slaves who fled to England and wrote an acclaimed book about their escape, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. Dr. Crum assisted Reverend William Henry Heard in organizing protests over the distribution of relief funds afterthe earthquake. He often spoke to groups about the dangers of fevers and other infectious diseases.

In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Dr. Crum collector of customs in Charleston, a post that gave him authority over white men. A storm of controversy erupted, and the fight over his confirmation became one of the most significant battles of Roosevelt's presidency. U. S. senator Ben Tillman blustered, "We still have guns and ropes in the South." James C. Hemphill, editor of the Charleston News and Courier, wrote that Crum “is a colored man, and that in itself ought to bar him from office.” Roosevelt resorted to a technicality, first to put Crum in office and then to keep him there--he made the appointment during a congressional recess, removing the need for Senate approval. He declared, "I cannot consent to take the position that the door of hope--the door of opportunity--is to be shut upon all men, no matter how worthy, purely on the grounds of color." But as soon as Roosevelt left the White House, the door of opportunity slammed. William Howard Taft became president in 1909, and he refused to reappoint Crum as collector of the customs. Instead, he proposed that Crum be made consul general to Liberia, a position traditionally given to a black politician. Crum accepted the job and moved to Monrovia with his wife. He had always been interested in infectious diseases, and he treated some of his colleagues for "African fever." In September 1912 Dr. Crum himself contracted African fever and returned to the United States, where he could get better medical care. Shortly after he reached Charleston, Dr. Crum died, a sacrifice, as one northern newspaper put it, "upon the altar of . . . Southern prejudice."

Alonzo Clifton McClennan

Alonzo Clifton McClennan was born in Columbia, SC, in 1855. After graduating from Howard University’s Schools of Medicine and Pharmacy, McClennan moved to Charleston in 1884 and established the first black drugstore, called the People’s Pharmacy, on King Street. He helped found the Hospital and Training School for Nurses and served as its medical director,surgeon-in-charge, and instructor in surgical nursing until his death in 1912.

Dr. McClennan edited the Hospital Herald—A Monthly Journal devoted to Hospital Work, Nurse Training and Domestic and Public Hygiene. In addition to writing about health-related matters, Dr. McClennan used the Hospital Herald to promote fundraising events such as community fairs, teas, and, in later years, radio-thons, a telethon and a “womanless” wedding featuring physicians. In one issue he wrote, “Every penny you give will do something toward the relief and suffering and toward training some deserving colored woman in an honorable and useful profession.”